Nature has been testing its systems for 3.8 billion years. It shows us how to stay productive under stress and recycle everything. Biomimicry in agriculture uses these lessons to improve farming.

In the United States, “resilient” farming means staying profitable through tough weather and rising costs. “Circular” farming aims to reduce waste by keeping nutrients and water on the farm. This approach uses nature’s wisdom while still meeting farming needs.

This article focuses on practical steps for farms to become more circular. It covers soil health, water use, biodiversity, and using data to reduce waste. It connects these ideas to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals for agriculture, making them accessible to farmers.

The article looks at different farming types across the United States. It recognizes that what works in one place might not work elsewhere. The goal is to design better farming systems that fit real-world challenges.

What Biomimicry Means for Resilient, Circular Agriculture

In farm talk, “nature-inspired” can mean anything from cover crops to clever marketing. Biomimicry in agriculture is more precise. It’s a design method that starts with a function, like holding water or cycling nutrients. It then looks at how nature already solves these problems.

The Biomimicry Institute and Biomimicry 3.8 helped set this standard. They keep biomimicry focused on real research and development, not just a green feeling.

Biomimicry vs. regenerative agriculture vs. agroecology

When comparing regenerative agriculture, the real difference is the job each framework does. Regenerative agriculture focuses on healthier soil and more biodiversity. Biomimicry, on the other hand, offers a method to design practices and systems.

The debate between agroecology and regenerative agriculture adds another layer. Agroecology uses ecological science and social context to shape farming. Biomimicry is more about inventing tools and systems based on nature.

| Framework | Main focus | What it tends to change on farms | How success is discussed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomimicry | Design process inspired by biology (function first) | System layout, materials, technologies, and management “rules” modeled on natural strategies | Performance against a function: fewer losses, stronger feedback loops, and lower waste |

| Regenerative agriculture | Outcomes for soil, water, carbon, and biodiversity | Cover crops, reduced disturbance, integrated grazing, and habitat support | Field indicators: aggregate stability, infiltration, nutrient efficiency, and resilience to stress |

| Agroecology | Ecological science plus social and economic realities | Diversified rotations, local knowledge, and governance choices across landscapes | System outcomes: productivity, equity, and ecological function at farm and community scale |

Resilience and circularity principles found in ecosystems

Nature runs efficiently without waste. Ecosystems rely on simple principles: nutrients cycle, energy cascades, and waste becomes feedstock. This translates to tighter nutrient loops and smarter use of residues on farms.

Resilience is about structure, not just slogans. Ecosystems build redundancy and diversity to avoid disasters. They use feedback loops for quick adjustments, not surprises at the end of the year.

- Redundancy to prevent single-point failure in crops, water, and income streams

- Distributed storage (carbon in soil and biomass) instead of one big “tank” that can leak

- Local adaptation that respects soil types, microclimates, and pest pressure

- Cooperation and competition balanced through habitat, timing, and spatial design

Why nature-inspired design fits U.S. farming realities

U.S. farms operate within rules and constraints. Crop insurance, USDA programs, and irrigation schedules shape decisions. Resilient farm design in the U.S. must work within these rules.

Biomimicry is valuable because it views constraints as design inputs. Nature outperforms human systems in waste elimination and risk control. By applying nature’s logic to farms, we can redesign field edges, adjust rotations, and rethink water flow.

Biomimicry resiliency agriculture circularity for United Nations SDGs

Biomimicry is like a strategy generator. Ecosystems test what works under stress. Farms aim for resilience and circularity, using the SDGs as a guide.

Farms face a big challenge. They must fight climate change, protect biodiversity, and keep costs low. Biomimicry helps by using nature’s designs to balance these needs.

How nature-based strategies map to SDG targets

Nature-based solutions align with SDG targets. They show clear results on the ground. For example, water-saving irrigation and healthier soils meet these targets.

| Biomimicry-aligned move | Farm outcome | SDG targets agriculture alignment | Typical proof point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape-style water routing (micro-catchments, contour thinking) | Higher irrigation water productivity during heat and dry spells | SDG 6 (water use efficiency, watershed protection) | Yield per acre-foot; pumping energy per acre |

| Soil as a “carbon bank” (aggregation, roots feeding microbes) | Soil organic matter gains with better infiltration | SDG 13 (climate mitigation and adaptation) | Soil organic carbon change; reduced runoff events |

| Habitat mosaics that mimic edge-rich ecosystems | More natural enemies; steadier pollination services | SDG 15 (life on land, biodiversity) | Pollinator habitat acreage; pesticide risk reduction index |

| Nutrient cycling modeled on closed loops | Lower losses of nitrogen and phosphorus; fewer waste costs | SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) | Nitrogen use efficiency; manure methane capture rate |

| Diversity for stability (varied rotations, mixed cover species) | Reduced yield swings; fewer “single point of failure” seasons | SDG 2 (productive, resilient food systems) | Multi-year yield stability; erosion risk score |

From on-farm outcomes to measurable sustainability indicators

Procurement programs want verified performance, not just good intentions. Sustainability indicators help turn field changes into numbers. These numbers are useful for audits and dashboards.

Metrics like nitrogen use efficiency and soil organic carbon change are key. They help farms meet ESG reporting requirements without becoming paperwork factories.

Where farms, supply chains, and policy intersect

Supply chains are setting higher standards. Food companies want quantified outcomes, not just claims. Sourcing programs need verification across seasons.

Policy affects what’s possible. USDA NRCS standards and climate pilots can help or complicate things. Biomimicry offers a clear path through this complexity, focusing on performance and risk.

Nature-Inspired Soil Health and Carbon Sequestration Strategies

In forests and prairies, soil acts like a living system. It holds shape, moves water, and keeps nutrients in balance. biomimicry soil health treats the field as a system, not a factory. It uses familiar strategies like less disturbance, more living roots, steady organic inputs, and rotations.

These methods help with carbon sequestration farming. But, they don’t follow a set schedule. Nature stores carbon slowly, while people want quick results. That’s why tracking progress is key.

Building living soils with fungal networks and aggregation analogs

Fungal networks in agriculture use thin hyphae like rebar. They bind particles and feed microbes, making sticky exudates. This creates stable soil crumbs that hold water and reduce erosion.

Management aims to protect this structure. It uses strip-till or no-till, keeps residue cover, and plans fertility carefully. This keeps pores connected, allowing for better movement of oxygen, roots, and nutrients.

Soil and Carbon Strategies Continuing

Cover crop “ecosystems” for nutrient cycling and erosion control

Cover crop ecosystems are like designed communities. Legumes provide nitrogen, grasses build biomass, and brassicas push roots into tight zones. They slow erosion and keep roots trading sugars with soil life longer.

This diversity spreads risk. One species may stall in cold springs, while another keeps growing. How and when you terminate cover crops affects soil temperature, weed pressure, and nutrient cycling.

Biochar and natural carbon storage models

Biochar soil carbon mimics long-lived carbon pools in stable soils. The recipe matters: feedstock, pyrolysis conditions, and application rates. Many growers blend or co-compost biochar to reduce early nutrient tie-up.

Verifying carbon sequestration farming claims is complex. Soil carbon changes with landscape, depth, and past management. Reliable accounting uses repeatable protocols and good field data.

| Nature-inspired lever | Field practice examples | What it changes in soil function | Verification and expectations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungal-driven structure (fungal networks agriculture) | Reduced disturbance; strip-till/no-till where appropriate; residue retention; biology-supportive fertility | Improves infiltration, aggregate stability, and drought buffering via mycorrhizae soil aggregation | Track infiltration, aggregate stability tests, and consistent SOC sampling depth over multiple seasons |

| Multi-species cover crop ecosystems | Legume–grass–brassica mixes; staggered seeding windows; termination matched to planting plans | Boosts nutrient cycling, reduces nitrate leaching risk, and limits wind/water erosion | Measure biomass, ground cover days, nitrate tests where used, and repeatable management records |

| Stable carbon analogs (biochar soil carbon) | Select verified feedstocks; match pyrolysis to goals; blend or co-compost; apply at agronomic rates | Adds persistent carbon forms and can improve nutrient retention depending on soil and blend | Document batch specs, application rate, and sampling design; expect gradual change, not instant miracles |

Water Efficiency and Drought Resilience Through Biomimicry

In the U.S. West, water use is under scrutiny. The Ogallala Aquifer’s decline shows the need for careful water use. Biomimicry teaches us to use water like nature does—capture, slow, sink, store, and reuse it.

Effective drought farming focuses on small improvements. It’s not about finding a single solution. Instead, it’s about reducing waste and using water wisely.

Fog harvesting, dew capture, and micro-catchment concepts

Nature can pull water from the air. Fog harvesting uses this idea to collect water near coasts. It’s useful for crops, young trees, and water for livestock.

Micro-catchments mimic desert landscapes. They slow down water flow and help plants absorb it. This method keeps water in the soil, even when the weather is unpredictable.

Keyline design, contouring, and watershed thinking inspired by landscapes

Landforms manage water naturally. Farms can learn from this. Keyline design uses earthworks to slow and spread water.

Contour farming also helps manage water. It uses grassed waterways and buffers to keep soil in place. This approach is part of conservation planning and local rules.

Soil moisture retention lessons from arid ecosystems

Arid areas cover the ground to prevent evaporation. Using mulch and organic matter does the same. This keeps the soil moist during dry times.

Ecological design works well with technology. Drip irrigation and scheduling save water. The goal is to keep water in the soil, not let it evaporate.

| Biomimicry-inspired tactic | How it saves water | Best-fit U.S. use case | Key constraint to watch |

|---|---|---|---|

| fog harvesting agriculture collectors and dew surfaces | Captures small, steady moisture inputs for on-site storage | Coastal or high-humidity zones; nurseries; remote stock tanks | Low yield in hot, dry interior air; needs cleaning and wind-safe anchoring |

| Micro-catchments and planted basins | Slows runoff; increases infiltration near roots | Orchard establishment; rangeland restoration; slope edges | Soil crusting or overflow on intense storms if sizing is off |

| keyline design farms earthworks and strategic ripping | Redistributes water across ridges and valleys; reduces concentrated flow | Mixed operations with pasture-crop rotations; rolling terrain | Requires skilled layout; mistakes can create gullies or wet spots |

| contour farming watershed management with buffers and waterways | Protects infiltration areas; reduces sediment and nutrient loss | Row crops on slopes; fields draining to creeks or ditches | Equipment passes and maintenance planning must match field operations |

| Soil cover, windbreaks, and organic matter building | Lowers evaporation; improves water holding capacity and infiltration | Dryland grains; irrigated systems aiming to cut pumping | Residue can affect planting and pests; timing matters for soil temperature |

Pollinator Support and Biodiversity-Driven Pest Management

In many U.S. farms, biodiversity is seen as just decoration. But it’s much more than that. It helps keep yields steady, protects against risks, and prevents one pest problem from ruining the whole season.

Pollinator habitat farms are built to attract and keep pollinators and predators. They offer food and shelter, helping these beneficial insects work well even when the weather is bad. It’s not just about beauty; it’s about managing risks.

“Ecosystem services” might sound like a fancy term, but the results are clear. Better pollination means more fruit and better quality. Natural enemies also help control pests, avoiding big problems after spraying.

In the world of beneficial insects, lady beetles, lacewings, and wasps are the heroes. They don’t replace scouting, but they help keep pest numbers low. This protects the quality and timing of crops.

Pest Management Continuing

Biomimicry pest control looks to nature’s edge-rich landscapes for inspiration. Features like hedgerows, prairie strips, and flowering borders offer shelter and food. They’re placed carefully to avoid disrupting farming activities.

Habitat corridors help connect these areas, making it easier for beneficial insects to move. The goal is a farm that works well, not just looks good.

Integrated pest management biodiversity is all about using nature’s help. First, you monitor and set thresholds. Then, you use diverse rotations, trap crops, and pheromone traps to control pests. Sprays are used only when necessary.

In the U.S., pollination is a big deal, especially in places like California almonds. But wild pollinators are also crucial, especially when honey bees can’t keep up with the demands of different crops and regions.

The cheapest pest control is often a balanced ecosystem; unfortunately, it doesn’t come in a jug with a label and an instant rebate.

| Design move | What it mimics in nature | On-farm benefit | Fit with IPM decisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hedgerows prairie strips | Edge habitat with continuous bloom and shelter | Steadier pollination and more predator habitat near crop rows | Supports prevention so thresholds are reached later |

| Beetle banks and grassy refuges | Ground cover that protects overwintering predators | More early-season predation on aphids and caterpillars | Reduces “first flush” pressure that triggers early sprays |

| Flowering field borders | Nectar corridors that fuel adult parasitoids | Stronger parasitic wasp activity and fewer secondary pest spikes | Improves biological control alongside scouting and trapping |

| Riparian buffers | Stable, moist microclimates with layered vegetation | Habitat for diverse beneficials and better water-quality protection | Helps keep interventions targeted by limiting field-wide flare-ups |

| Habitat corridors farmland | Connected travel routes across mixed vegetation | Faster recolonization after disturbance and better season-long stability | Pairs with selective products to preserve natural enemies |

Circular Nutrient Systems and Waste-to-Value Farm Loops

In circular nutrient systems, the aim is to keep nutrients moving with little loss. Ecosystems do this naturally. Farms must design and follow rules to achieve this.

The best loops treat waste as a valuable resource. They track nutrients and manage risks. This approach ensures nutrients are used efficiently.

Manure, composting, and anaerobic digestion in closed-loop models

Manure management through anaerobic digestion turns waste into biogas. The leftover digestate must be stored and applied carefully. The success depends on permits, distance, odor control, and nutrient matching.

Composting Strategies

Composting farm waste is a slower but steady method. It stabilizes organic matter and reduces pathogen risk. Proper management of moisture, aeration, and carbon-to-nitrogen ratio is key.

| Loop option | Primary output | Key management levers | Common watch-outs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composting farm waste | Stabilized compost for soil structure and biology | Moisture control, oxygen flow, C:N ratio, curing time | Off-odors if too wet; nutrient loss if piles run hot and unmanaged |

| Manure management anaerobic digestion | Biogas/RNG plus digestate nutrients | Feedstock consistency, digester temperature, solids separation, storage planning | Permitting timelines; nutrient over-application if digestate is treated as “free” |

| Direct manure use with safeguards | Fast nutrient supply with organic matter | Application timing, incorporation method, setback distances, weather windows | Runoff risk during storms; volatilization losses when left on the surface |

On-farm nutrient recapture and precision placement

Nutrient recapture starts with soil tests and ends with precise application. This ensures nutrients are used efficiently. Variable-rate application and controlled-release products help.

In irrigated systems, fertigation keeps nitrogen doses small. Edge-of-field practices like wetlands and buffers also help. They keep nutrients from leaving the farm.

Byproduct valorization across local supply chains

Waste-to-value agriculture uses materials beyond the farm. Brewery spent grain and cotton gin trash can be used. Rice hulls and food processing residuals also have value.

Local supply chain byproducts include green waste. It can boost compost volumes if managed well. Logistics and specifications are key to turning waste into valuable inputs.

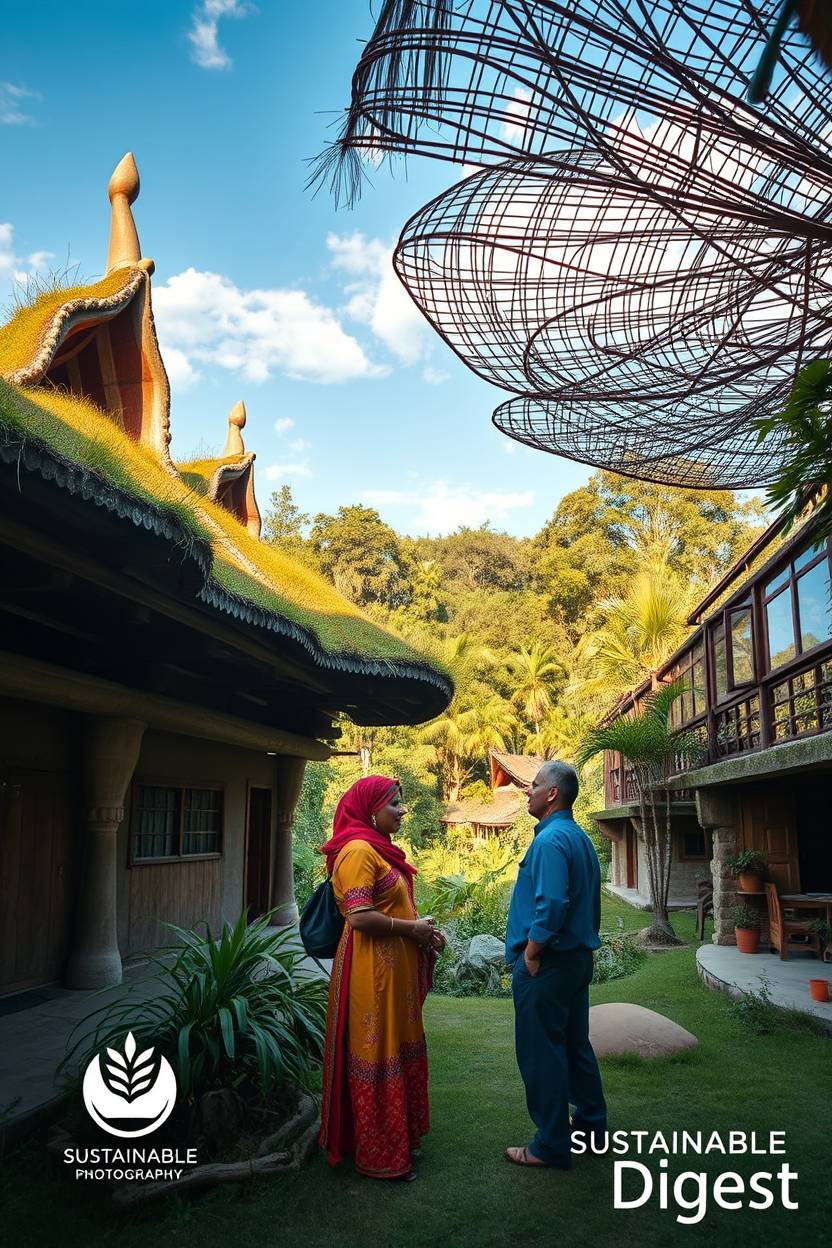

Biomimicry in Farm Design, Materials, and Infrastructure

In agriculture, the biggest problem is often not the crop. It’s the buildings that get too hot in summer or flood in spring. Biomimicry makes barns, pack sheds, and storage work like systems, not just buildings. By managing heat, wind, and water, downtime and repairs decrease.

Passive design leads to smart solutions. Barns can use the design of termite mounds to stay cool. They have tall paths for hot air to leave and cool air to enter, without big fans.

Greenhouse design mimics nature by controlling light and humidity. The right colors and textures can reflect sun like desert plants. This reduces stress on plants and keeps workers safe.

Choosing materials is key because a building’s impact is tied to its supply chain. Nature-inspired materials use smart designs to be strong yet light. This approach is good for the planet and keeps buildings safe and clean.

Circular materials are also important. Designing for easy disassembly and repair helps keep materials in use. This is practical when parts are hard to find and budgets are tight.

Biomimicry adaptation continuing

| Design move | Natural analog | Where it fits on U.S. farms | Operational value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stack-driven ventilation paths | Termite mound airflow channels | passive cooling barns, commodity storage, milk rooms | Lower heat stress; steadier air quality with fewer moving parts |

| High-reflectance surfaces and timed shade | Desert species that reduce heat absorption | greenhouse design biomimicry, shade structures, equipment shelters | Reduced peak temperatures; less HVAC demand during heat waves |

| Geometry-led strength | Bone lattices and honeycomb efficiency | sustainable farm buildings, retrofitted trusses, modular partitions | Material savings; easier handling; fewer structural failures |

| Design for disassembly and reuse | Ecosystems that cycle nutrients without waste | Wall panels, flooring, roofing, interior fit-outs | Faster repairs; lower waste; supports circular materials planning |

Energy is as important as walls and roofs. Solar power and small grids can support farm infrastructure. They help when fuel prices rise or the grid fails.

Most farms can’t start over, and no one has time for big changes. Small upgrades like better airflow and insulation make a big difference. These changes bring nature’s wisdom into everyday farm life.

Technology and Data: Biomimetic Innovation in AgTech

In resilient, circular farming, technology is like a nervous system, not just a display of dashboards. biomimetic AgTech focuses on feedback, aiming to sense changes early and respond quickly. It also tries to waste less. Nature does this without needing weekly meetings, which seems like a missed chance for most software.

Swarm intelligence for robotics, scouting, and logistics

Swarm robotics agriculture takes cues from ants, bees, and birds. It uses many small agents with simple rules for steady coordination. In fields, this means multiple lightweight machines scouting, spot-spraying, or moving bins with less compaction than one heavy pass.

This approach often leads to timeliness. It catches weeds or pests early, before they become a big problem. Decentralized routing also helps when labor is tight and schedules slip. A swarm can split tasks across zones, then regroup as conditions change.

This flexibility supports adaptive management farming. Operations can shift without rewriting the whole playbook.

Sensor networks modeled on biological feedback systems

Organisms survive by sensing and responding; farms can do the same with sensor networks. Soil moisture probes, canopy temperature, sap flow, on-site weather stations, and nutrient sensors guide irrigation and fertility decisions. The goal is a tight loop: measure, interpret, adjust, and verify.

But data is not always truth. Calibration, placement, and interoperability matter. A drifted probe can “prove” a drought that is not there. Strong farm sensor networks treat maintenance like agronomy—routine, logged, and worth the time.

| Signal captured | Common field tools | Operational decision supported | Credibility check that prevents bad calls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root-zone water status | Soil moisture probes; tensiometers | Irrigation timing and depth by zone | Seasonal calibration; compare with shovel checks and ET estimates |

| Plant heat stress | Canopy temperature sensors; thermal imagery | Trigger cooling irrigation; adjust spray windows | Account for wind and humidity; validate with leaf condition scouting |

| Plant water movement | Sap flow sensors | Detect stress before visible wilt | Baseline each crop stage; flag outliers for field inspection |

| Microclimate risk | On-farm weather stations | Frost prep; disease pressure windows | Sensor siting standards; cross-check with nearby station patterns |

| Nutrient dynamics | Nitrate sensors; EC mapping; lab sampling | Split applications; prevent losses after rain | Pair sensors with lab tests; document sampling depth and timing |

AI decision support for adaptive management and risk reduction

precision agriculture AI merges forecasts, soil readings, pest pressure, and equipment limits to suggest practical options. Used well, it supports scenario planning and early warnings. This is risk reduction agriculture technology at its best: fewer surprises, fewer rushed passes, and fewer expensive “fixes” later.

The fine print is governance. Data ownership terms, vendor lock-in, and algorithm transparency shape whether insights can be trusted, shared, or audited. For sustainability claims and SDG-aligned reporting, defensible data trails matter. Adaptive management farming depends on knowing what was measured, how it was modeled, and who can verify it.

UN SDGs Impact Pathways for U.S. Agriculture

Impact pathways make the SDGs feel less like a poster and more like a scorecard. In SDGs U.S. agriculture, the pathway usually starts on the field, then moves through the supply chain, and ends in the county budget (where reality keeps excellent records). Biomimicry fits here because it turns ecosystem logic into repeatable farm decisions; less hype, more feedback loops.

To track progress, it helps to watch three kinds of change at once: operations, markets, and community outcomes. When those signals move together, the SDGs stop being abstract and start acting like a shared language that lets USDA programs, state agencies, and corporate buyers briefly pretend they speak the same dialect.

SDG 2, SDG 12, and SDG 13

For SDG 2 zero hunger farming, the pathway is resilient yields plus stable nutrition supply; that often depends on soil structure, root depth, and pest balance, not just a bigger input bill. Biomimicry nudges farms toward redundancy (diverse cover mixes, living roots, and habitat edges) so a bad week of weather does not become a bad year of production.

SDG 12 circular economy food systems shows up when farms and processors treat “waste” as a misplaced resource. Manure becomes energy or compost, crop residues become soil cover, and byproducts find feed or fiber markets; the system keeps value moving instead of paying to haul it away.

SDG 13 climate action agriculture is easier to track than it sounds: fuel use, nitrogen efficiency, methane management, and soil carbon trends. Biomimicry-aligned practices can support that pathway by cutting passes, tightening nutrient cycles, and building soils that hold more water and carbon at the same time.

SDG 6 and SDG 15

SDG 6 water stewardship is not only about irrigation tech; it is also about what leaves the field when rain hits bare ground. Micro-topography, residue cover, and aggregation reduce runoff and keep nutrients on-site, which matters for watershed protection and downstream treatment costs.

SDG 15 biodiversity agriculture can be measured on working lands without turning every acre into a museum. Habitat strips, flowering windows, and lower chemical pressure can support beneficial insects and birds; the trick is designing “land sharing” so it protects function (pollination, pest control, soil life) while staying operationally realistic.

Equity, livelihoods, and rural resilience

Rural livelihoods rise or fall on cash flow, labor, and time, not on slogans. Adoption often hinges on whether technical assistance is available, whether verification is sized for small and mid-sized farms, and whether lenders and buyers recognize the risk reduction that comes with healthier soils and tighter cycles.

Programs can also tilt toward larger operations if reporting costs too much or if incentives arrive late. A practical pathway keeps paperwork proportional, aligns with conservation cost-share, and leaves room for co-ops, local processors, and community colleges to support training that sticks.

UN Sustainable Development Goals adaptation to agriculture

| Impact pathway | On-farm change | Supply chain change | Community signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 2 zero hunger farming | Diverse rotations and cover crops to stabilize yields; improved soil tilth for root access during stress | More consistent volume and quality for mills, dairies, and produce buyers; fewer emergency substitutions | Lower volatility in local food availability; steadier farm employment through the season |

| SDG 12 circular economy food systems | Composting, manure management, and residue retention; byproduct separation for higher-value use | Contracts for byproduct utilization (feed, fiber, energy); less disposal and shrink loss | Reduced landfill pressure; new service jobs in hauling, composting, and maintenance |

| SDG 13 climate action agriculture | Fewer field passes and tighter nitrogen timing; options to cut methane via digestion or improved storage | Lower embedded emissions per unit; clearer reporting for corporate sustainability commitments | Improved air quality and energy resilience where on-farm generation is feasible |

| SDG 6 water stewardship | Better infiltration from cover and aggregation; irrigation scheduling that matches crop demand | More reliable water allocation planning for processors; fewer disruptions from water restrictions | Lower sediment and nutrient loads; reduced stress on shared wells and municipal treatment |

| SDG 15 biodiversity agriculture | Habitat design (field borders, flowering strips); reduced broad-spectrum pesticide pressure | Fewer pest outbreaks and rejections tied to residue risk; more stable integrated pest management programs | Healthier working landscapes that support recreation and ecosystem services without removing production |

| rural livelihoods | Lower input dependency over time; management skills shift toward monitoring and adaptation | Fairer premiums when verification is right-sized; stronger local processing and aggregation options | More durable rural businesses; better odds that young operators can stay in the game |

Implementation Roadmap: From Pilot Plots to Scaled Adoption

In biomimicry implementation agriculture, starting small is key. A few acres can serve as a “test ecosystem.” Here, results are tracked before expanding to the whole operation. This approach avoids expensive surprises.

A regenerative transition roadmap starts with a baseline. This includes soil structure, infiltration, and nutrient losses. Goals are set using clear indicators like input intensity and biodiversity signals.

Pilot projects focus on one challenge at a time. For example, a cover-crop mix for nutrient cycling or a habitat strip for beneficial insects. Each intervention needs a monitoring plan with seasonal checks.

| Step | What gets done | What gets measured | Risk control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Sample soil, review irrigation logs, map erosion and compaction zones | Organic matter, infiltration, nutrient balance, fuel and input use | Use existing records first; add tests only where decisions depend on them |

| Design | Select biomimicry-inspired practices for soil, water, habitat, and nutrient loops | Practice cost, labor hours, equipment fit, timing windows | Match changes to the least disruptive pass through the field |

| Pilot | Run side-by-side strips and keep operations consistent elsewhere | Stand counts, weed pressure, irrigation need, yield stability | Limit acreage; keep a “reset” option for the next season |

| Iterate | Adjust mixes, rates, and placement; refine scouting and thresholds | Trend lines across seasons; variance by soil type and slope | Change one variable at a time to avoid false wins |

| Scale | Expand only what performs; standardize reporting and training | Whole-farm input reduction, profit per acre, risk metrics | Phase capital purchases; keep vendor contracts flexible |

Implementation continuing

To scale circular agriculture practices, economics must be tracked with the same discipline as agronomy. ROI conservation practices often shows up as fewer passes, steadier yields, lower fertilizer losses, and less rework after heavy rain. Financing can mix NRCS cost-share, supply-chain incentives, and carbon or ecosystem service programs; permanence and verification still deserve a skeptical look.

Real change management farms plans for friction: equipment limits, narrow planting windows, a learning curve in scouting, and short-term yield swings. Tenant-landlord dynamics can also slow decisions, since the payback may land in a different pocket. Practical fixes include phased capital investments, custom operators, Extension support, and technical service providers who reduce the reporting burden.

Scaling also means coordinating beyond the fence line. Circularity rarely works if processors, livestock integrators, input suppliers, and municipalities are not aligned on byproducts, organic residuals, and hauling schedules. That coordination is less romantic than a meadow; it is still the part that makes the system hold together.

Conclusion

Farms do better when they work like ecosystems. Biomimicry solutions in agriculture use nature’s ways to improve farming. The UN SDGs help by making results clear to everyone.

In the United States, sustainable farming is about practical steps. Nature-based solutions help farms face drought, erosion, and unpredictable weather. They also make farming less dependent on expensive inputs and long supply chains.

The best strategy for sustainable farming starts small and is true to itself. Begin by tackling one problem, like soil compaction or pests. Then, test nature-inspired solutions and see what works. This way, farming becomes more resilient through learning and improvement.

Nature teaches us to keep trying and adapting. Biomimicry in agriculture follows this approach. It leads to better food systems and a stronger, more sustainable farming future in the United States.

Key Takeaways

- Biomimicry in agriculture borrows operating principles from ecosystems without pretending farms are wilderness preserves.

- Resilient farming systems in the United States focus on risk: climate volatility, inputs, water, labor, and market demands.

- Circular agriculture solutions aim to keep nutrients, water, and carbon cycling on-farm to reduce losses and costs.

- Nature-inspired innovation can complement agronomy through smarter soil, water, biodiversity, and infrastructure choices.

- UN Sustainable Development Goals agriculture offers a shared framework for reporting that increasingly shapes buyers and capital.

- The article connects biology-inspired ideas to measurable outcomes across sustainable food systems United States regions.