Every third Thursday of February, global professionals recognize the rich diversity of our species. This event, formally launched in 2015, promotes a discipline that examines human social systems across time. It serves as a reminder that humanity is both deeply rooted in history and focused on our shared future.

The integration of World Anthropology Day Sustainability Archaeology Internationalism highlights a shift toward practical global action. Experts now use these combined insights to address resource scarcity and social inequality within Sustainable Reporting Frameworks. Ironically, ancient survival strategies are becoming the most advanced tools for modern environmental stewardship.

Adopting a holistic lens allows us to bridge grassroots efforts with the United Nations goals. By valuing traditional wisdom, we can better navigate the complexities of global cooperation. This perspective ensures that future development remains grounded in actual human experience rather than just abstract data.

What World Anthropology Day Represents in Today’s Global Context

Beyond the dusty shelves of university libraries, world anthropology acts as a lens through which we can examine the mechanics of modern society. This discipline offers more than just historical facts; it provides a roadmap for navigating a complex, interconnected world. By studying the human field of experience, we gain the tools to address cultural friction and environmental decay with precision.

The Origins and Mission of World Anthropology Day

The American Anthropological Association introduced Anthropology Day in 2015 to bridge the gap between academic research and public awareness. What began as a domestic initiative quickly evolved into an international movement involving various institutions. Today, the anthropological association encourages groups to showcase how their work impacts real-world policies and local communities.

Every February, scholars from the United Kingdom to Australia organize forums to celebrate world anthropology and its diverse applications. This american anthropological effort transformed a private academic discourse into a public dialogue about our shared future. By democratizing knowledge, the anthropological association ensures that human insights are accessible to everyone, not just those in ivory towers.

The Four Branches: Cultural, Biological, Archaeological, and Linguistic Anthropology

The study of humanity is traditionally split into four primary branches that function as complementary tools. These branches allow us to reconstruct past civilizations while simultaneously analyzing how modern language shapes our current identity. Each subfield contributes a unique piece to the puzzle of human evolution and social development.

- Cultural Anthropology: Examines social practices, traditions, and how communities organize their belief systems.

- Biological Anthropology: Investigates human evolution, genetics, and our physical adaptation to different environments.

- Archaeology: Uncovers the material remains of past cultures to understand their resource management.

- Linguistic Anthropology: Explores how communication styles reflect and build social structures.

Why Anthropology Matters for Contemporary Global Challenges

Modern anthropology is uniquely positioned to solve the riddle of sustainability. While climatologists provide the data on rising tides, the american anthropological perspective provides the cultural context needed for community-led adaptation. World Anthropology Day highlights this shift from mere observation to active participation in solving resource conflicts.

By using the american anthropological association framework, experts can translate global sustainability goals into local actions that respect cultural autonomy. This annual anthropology day reminds us that a sustainable future requires a deep understanding of our biological and cultural past. It is through this holistic view that world anthropology day proves its immense value in an era of rapid environmental change.

| Anthropology Branch | Primary Focus | Contribution to Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| Archaeological | Material Remains | Analyzing past climate resilience and resource failures. |

| Cultural | Social Dynamics | Documenting traditional ecological knowledge and practices. |

| Biological | Human Adaptation | Studying physiological responses to environmental stress. |

| Linguistic | Communication | Understanding how cultures conceptualize nature and conservation. |

Archaeology as a Window into Human Sustainability Practices

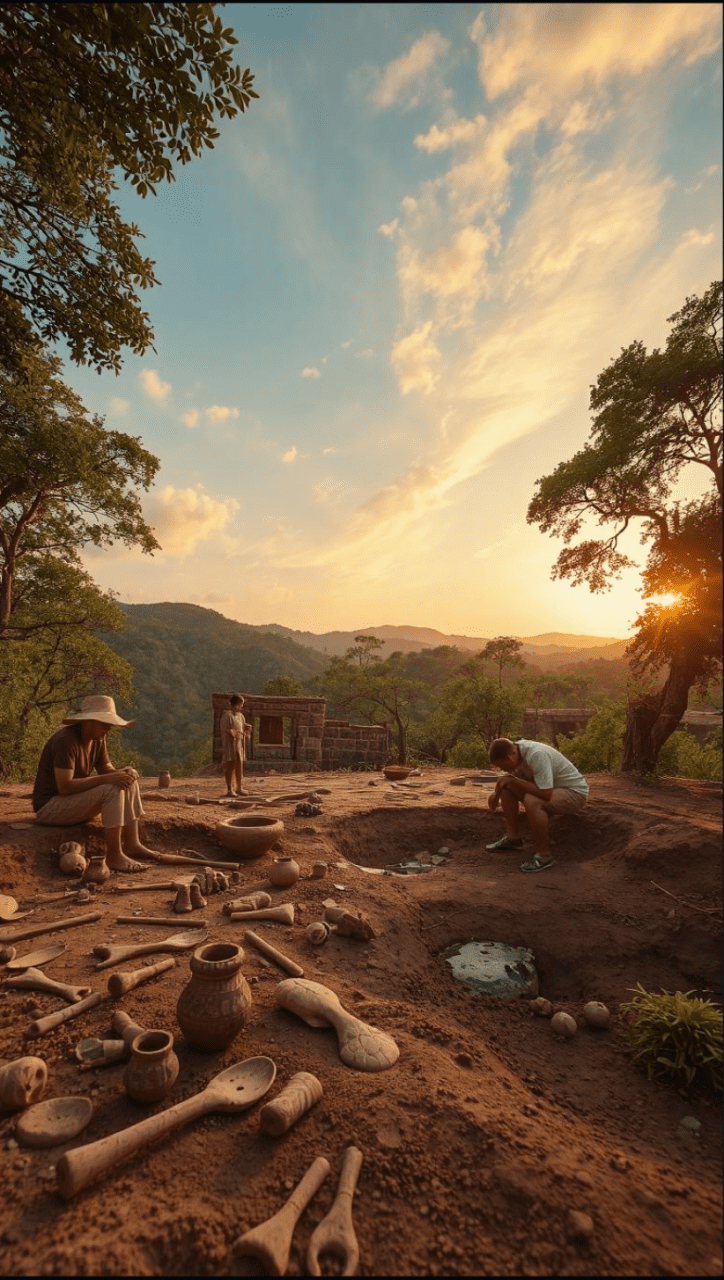

Modern sustainability often looks like a new idea, but archaeology proves it is a long-standing human tradition. As a core branch of anthropology, archaeology uncovers material evidence of past civilizations through careful excavations. These findings reshape our history and reveal how we have always interacted with the planet.

Archaeological Evidence of Ancient Environmental Management

Recent research shows that sustainability is less of a modern invention and more of a vital rediscovery. From Mesopotamian irrigation to Polynesian aquaculture, ancient societies developed sophisticated resource management systems. They spent generations observing their environments to create solutions that lasted for centuries.

Indigenous terracing in the Andes prevented soil erosion more effectively than many modern agricultural tools. Such anthropology highlights that ancient knowledge often rivals our contemporary technical understanding. These systems were built on necessity, proving that necessity is indeed the mother of green innovation.

Material Culture Studies and Resource Conservation Patterns

Studying material culture gives us tangible proof of how past people conserved their limited resources. Long before “circular economy” became a popular term, various cultures used pottery and building designs that minimized waste. These patterns of repair and reuse offer a sharp contrast to our modern habits of disposability.

Archaeologists examine tool assemblages to find evidence of adaptive experimentation. This research uncovers how humans modified their behavior to fit environmental constraints. It reminds us that our anthropology is defined by our ability to adjust our footprints.

Lessons from Past Civilizations: Collapse and Resilience

Scholars analyze the history of the Maya and Easter Island to find cautionary tales regarding ecological limits. These societies provide clear warnings about what happens when we exceed the earth’s carrying capacity. However, resilient communities also provide a clear blueprint for long-term survival.

Understanding our origins helps humans maintain the evolution of social organization needed to thrive. By looking at these traditions, we can build more resilient policies for today’s climate challenges. The past is not just a record; it is a living lesson in endurance.

“Archaeology provides the long-term perspective necessary to understand the human impact on the environment over millennia.”

| Ancient Practice | Sustainable Benefit | Modern Insight for People |

|---|---|---|

| Andean Terracing | Prevents soil erosion | High-altitude farming efficiency |

| Mesopotamian Irrigation | Controlled water flow | Drought-resistant infrastructure |

| Polynesian Aquaculture | Renewable food sources | Circular marine management |

World Anthropology Day Sustainability Archaeology Internationalism: The Convergence

The intersection of world anthropology day sustainability archaeology internationalism represents a clear plan for tackling our planet’s hardest tasks. This meeting of ideas shows how anthropology acts as a bridge between the past and our future.

By blending ancient findings with modern data, we can better understand how humans survive change. It is not just about bones; it is about building a lasting world for everyone.

Integrating Anthropological Disciplines for Holistic Understanding

A holistic study requires more than just one perspective to be effective. When biological scholars examine physical adaptation and archaeologists analyze ancient societies, we gain a complete picture of human strength.

This integrated approach ensures that modern research reflects the complexity of our global systems. We can see how environment and culture work together over long periods.

| Discipline | Contribution | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Archaeology | Historical Data | Long-term resilience |

| Biological | Physical Evidence | Human adaptation |

| Cultural | Social Patterns | Resource management |

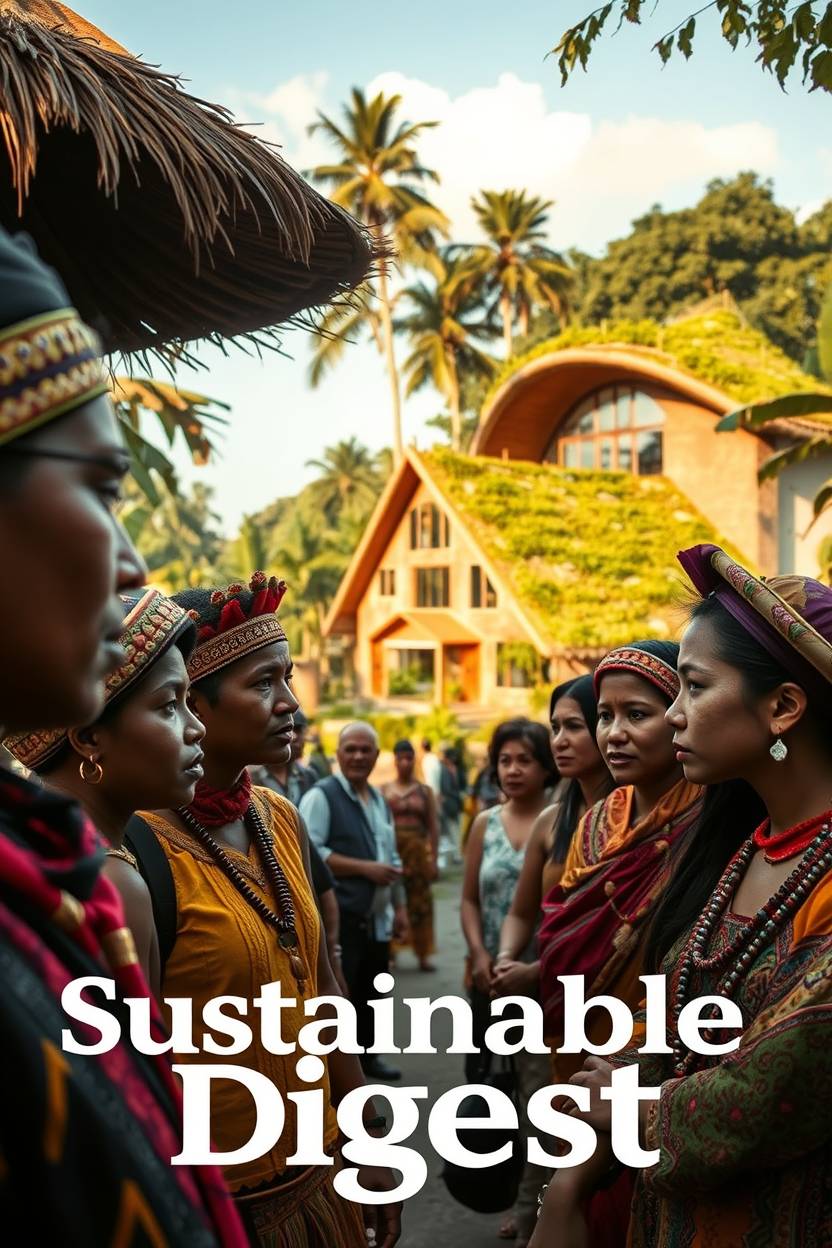

Cross-Cultural Environmental Knowledge and Global Solutions

Indigenous cultures have managed ecosystems for thousands of years through direct experience. By celebrating anthropology day, we acknowledge that traditional knowledge often provides the best answers to modern environmental issues.

These time-tested systems offer viable alternatives to industrial models that often fail. Learning from the land is a lesson we cannot afford to ignore any longer.

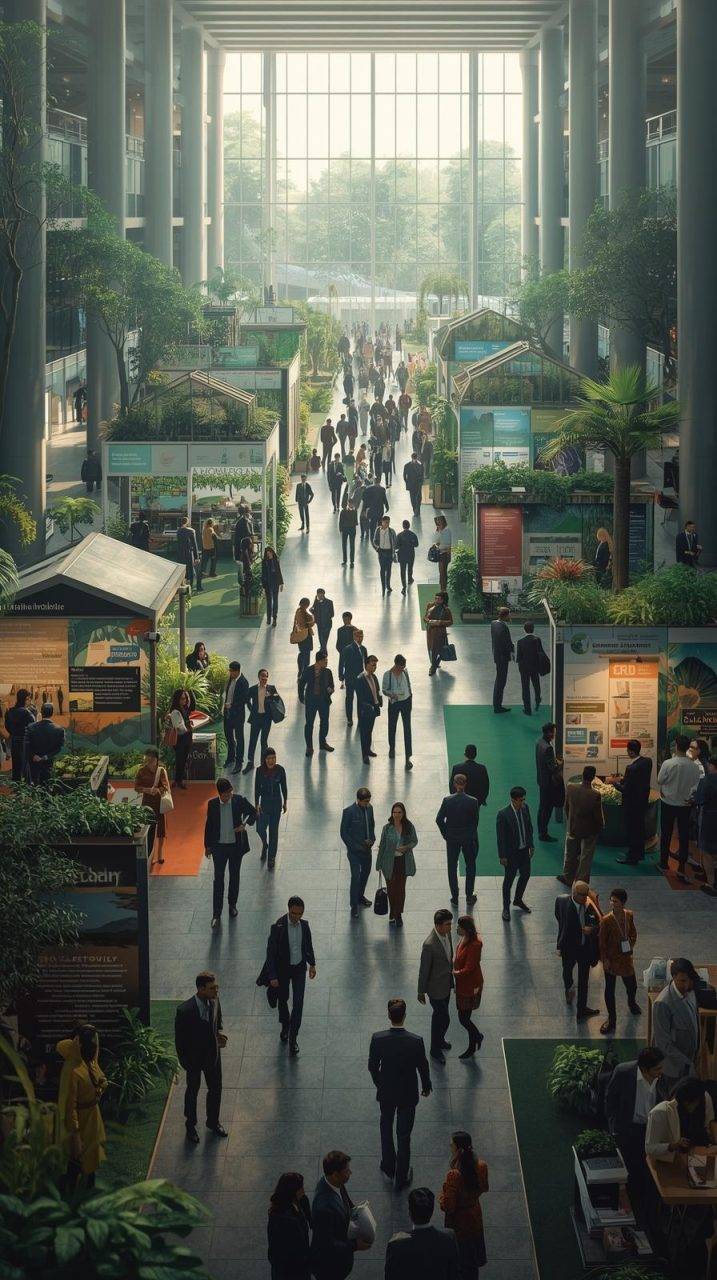

International Collaboration in Anthropological Research Networks

Global challenges like climate change do not stop at national borders. This anthropology day reminds us that research networks allow people from different regions to share their best survival strategies.

Strong ties between societies help us develop shared solutions while keeping local identities alive. Global anthropology thrives when we work across borders to solve common problems.

Bridging Local Practices with Global Sustainability Goals

Effective development must respect the local context to succeed over the long term. This world anthropology day, we focus on how anthropology ensures global goals align with actual community needs.

A careful study of human behavior leads to sustainable development that truly benefits everyone. It avoids the mistakes of top-down rules that ignore the reality of daily life.

Anthropology’s Critical Role in Advancing Environmental Sustainability

While engineers design massive sea walls, anthropologists study the human communities living behind them to ensure sustainability actually functions. This specialized field moves beyond cold data points to reveal the human heartbeat of environmental resilience. By examining the complex relationship between societies and their surroundings, anthropology provides the cultural context necessary for survival in a changing world.

Modern anthropology proves that human behavior is just as important as biological data when protecting our planet. Understanding how people perceive their surroundings allows for more effective conservation strategies that residents will actually support.

Climate Change Adaptation Through Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Indigenous groups have observed their environments for generations, developing a deep understanding of natural cycles. This traditional ecological knowledge is a vital, yet often ignored, resource for modern climate strategies. By documenting these systems, anthropologists help integrate local wisdom into global frameworks that often rely solely on Western science.

Cultural Anthropology and Modern Environmentalism

The study of human culture reveals that “nature” is often a social construct. Many Western conservation models attempt to create “pristine” zones by removing local inhabitants. However, this work shows that collaborative stewardship usually yields better results than displacement.

Ethnographic Research Informing Environmental Policy

Long-term research provides a ground-level view of how policies impact daily life. For instance, understanding climate-induced migration requires looking at political issues and social inequality rather than just rising tides. This perspective ensures that regulations are fair and effective for the people they affect most.

Moreover, experts in public health explore how environmental degradation affects community health. By working with various institutions, these professionals ensure that policies address real-world challenges rather than theoretical models. Their work bridges the gap between high-level governance and the practical needs of local populations.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and Anthropological Practice

The 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) serve as a complex blueprint for humanity. While these objectives address global crises, their success depends on more than just technical data. Achieving these targets by 2030 requires the deep cultural insight that anthropology provides to bridge the gap between policy and practice.

How Anthropology Supports Achievement of the 17 UN SDGs

Professional anthropologists translate high-level global aspirations into locally appropriate actions. They advocate for progress that respects cultural diversity rather than imposing a single Western model of development. By analyzing how different societies organize themselves, researchers ensure that international aid remains relevant and effective.

Poverty, Health, and Education Goals Through Cultural Lens

Goal 1 seeks to end poverty, yet the definition of “well-being” varies across the globe. Some cultures prioritize communal wealth over individual material gain. In the realm of public health (SDG 3), initiatives thrive when they integrate biomedical science with local healing traditions and health beliefs.

Environmental SDGs and Anthropological Insights

Goals focused on climate action and clean water benefit from studying traditional ecological knowledge. This work highlights how indigenous communities have managed resources sustainably for centuries. These ancient patterns offer modern solutions for responsible consumption and land conservation.

Cultural Sensitivity in Implementing Global Development Initiatives

Cultural sensitivity involves restructuring the traditional power dynamics found in international development. Instead of viewing local people as passive recipients, anthropologically-informed models treat them as the primary experts of their own lives. This shift prevents the “one-size-fits-all” failures that often plague top-down interventions.

Participatory Development and Community-Based Approaches

On the third thursday february, the academic and professional community celebrates World Anthropology Day. This annual day serves as a platform where students host events to share research with the general public. These showcases prove that participatory methods lead to more equitable and lasting global solutions.

- Participatory Design: Ensuring communities lead the planning of local infrastructure.

- Ethical Engagement: Prioritizing research reciprocity and long-term community autonomy.

- Critical Evaluation: Questioning if “growth” must always follow Western economic patterns.

Anthropology is the only discipline that can provide the human-centric data needed to turn the SDGs from a wish list into a reality.

Sustainable Reporting Frameworks, Standards, and Anthropological Perspectives

Sustainable reporting standards frequently quantify nature while accidentally overlooking the complexity of human societies. Standardized systems like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) provide the skeleton of sustainability, but anthropology provides the essential muscle. By examining how corporations impact traditions, experts ensure that reports reflect more than just financial data.

These frameworks often ignore the qualitative dimensions of social impact and community wellbeing. Meaningful assessment must capture the disruption of local life that numbers cannot show. Anthropologists provide the necessary lens to see these hidden human costs.

Understanding Corporate Sustainability Reporting Through Human Context

Corporate reports usually focus on measurable outputs like carbon emissions or water saved. However, these metrics often neglect the culture and the lived experience of the people involved. They fail to ask if resource extraction disrupts the daily life of the community.

Experts ask whether new economic opportunities disrupt existing social systems or support them. They look at how employment affects local power dynamics and family life. This approach ensures that corporate growth does not come at the expense of local stability.

GRI Standards and Social Impact Assessment

GRI Standards remain the most popular framework for reporting social impact today. While these studies track compliance with universal norms, they may fail to assess actual community wellbeing. They often record that a meeting happened without asking if it was culturally appropriate.

Standardized metrics often miss the difference between documenting a consultation and evaluating its genuine influence on the community.

A deep study explores whether a company truly respects humanity beyond just checking boxes for the media. It looks at human rights and labor practices through a local lens. This prevents corporations from imposing foreign models on local populations.

Anthropological Methods for Measuring Cultural and Social Sustainability

Measuring sustainability requires more than brief surveys; it demands rigorous research and participant observation. These qualitative studies capture the nuance and history that numerical data often ignores. This long-term engagement reveals the contradictions that simple surveys miss.

| Reporting Element | Traditional Metric | Anthropological View |

|---|---|---|

| Social Impact | Number of Jobs Created | Impact on Social Status |

| Engagement | Quantity of Meetings | Quality of Communication |

| Sustainability | Resource Efficiency | Preservation of Heritage |

By using ethnographic methods, researchers identify unintended social consequences of business. They help develop strategies that respect cultural autonomy and long-term resilience. This level of detail is rare in traditional reports but is increasingly necessary.

Stakeholder Engagement and Community Voice in Reporting

The language used in sustainability reports often carries cultural assumptions that lead to misunderstandings. Terms like “development” or “progress” may not translate well across different cultural contexts. Students attending World Anthropology Day events learn how to bridge these gaps between corporate and local interests.

Graduates now find diverse paths in international development, public health, and corporate consulting. They use their skills to ensure diversity is respected while following modern reporting systems. By including community voices, reporting becomes a tool for genuine empowerment for all humans.

Applied studies show that communities have their own criteria for success. They might value spiritual connections to land over economic gain. Respecting these diverse viewpoints is the only way to achieve true global sustainability.

Conclusion

Far from being a dusty academic pursuit, world anthropology day reveals how our shared origins guide us toward international cooperation and resilience. It is a vibrant celebration of humanity and the incredible diversity of our shared story. This discipline provides a vital framework to understand our world through multiple scientific and cultural lenses.

We look at the deep history of human evolution within the field of biology. We also study the complex nuances found in linguistic anthropology. Practitioners of linguistic anthropology help bridge communication gaps in global development. Observed on the third thursday february, this day fosters global awareness of how anthropologists tackle modern crises.

By merging world anthropology with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, we connect ancient archaeology with modern environmental resilience. Anthropology ensures that international reporting frameworks respect local traditions. This approach helps us pursue collective sustainability goals with expert precision and cultural sensitivity.

As we move forward, world anthropology will use technology to see how globalization reshapes identity. It is a special day for reflection on our collective future. Celebrating anthropology day reminds us that our past is the ultimate key to our survival in a changing climate.

| Focus Area | Anthropological Integration | Global Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | Linking ancient resource management to modern conservation patterns. | Enhanced environmental resilience and policy justice. |

| Internationalism | Applying ethnographic research to the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals. | Increased cultural sensitivity in global development initiatives. |

| Social Reporting | Utilizing social impact assessments to measure community well-being. | More transparent and human-centric corporate reporting standards. |

Key Takeaways

- Integrating ancient human history with modern ecological goals for better results.

- Moving beyond academic theory into practical global policy and development.

- Recognizing the third Thursday of February as a vital annual milestone.

- Using cultural insights to address current resource depletion and scarcity.

- Linking local practices to international sustainability reporting and frameworks.

- Enhancing social equity through holistic and historical research methods.